design: studiovrijdag.nl

website: emazing.nl

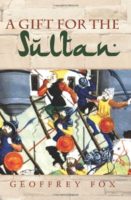

A Gift for the Sultan

Fiction

A Byzantine princess is snatched and entrusted to a fierce Ottoman warrior to deliver to the sultan as part of a surrender package of the city, until an unexpected overturn of the political chessboard changes all their fates.

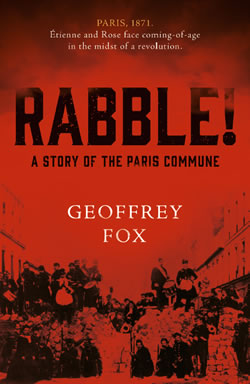

Rabble!

Fiction

Honor/shame in Cuba

Non-fiction

As a twenty-four-year-old black construction worker complained: “Nowadays the woman in Cuba almost rules herself and sometimes they rule her from outside. Neither the father, nor the mother nor the husband rules her.”

(From “Honor, Shame, and Women’s Liberation in Cuba: The Views of Working-Class Émigré Men,” 1973)