Guernica, 80 years on

Today, 26 April 2017 is the 80th anniversary of the German bombardment of the small Basque town of Gernika — “Guernica” in Spanish. And on this day we spent hours seeing and studying in context the presentation of Pablo Ruiz Picasso’s painting Guernica in the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid.

Weeks before the attack on Gernika, Picasso had agreed to produce a painting for the Spanish Pavilion in the International Exposition in Paris that spring of 1937. Though long established in Paris, Picasso was the most famous living Spanish artist and a known supporter of the Spanish Republic.

However, as he told Max Aub, who had invited him on behalf of the Government of the Spanish Republic, he had doubts about being able to produce anything useful in time of war against the fascist insurgency begun the year before, led by General Francisco Franco and supported by the great Nazi and Fascist powers, Germany and Italy. Picasso had never used his painting or sculpture to denounce or promote a social or political cause. And his works, explicitly or implicitly, had always implied an interior space — no landscapes, and certainly no battle scenes. Rather, his work since his cubist period had been an expression of his personal dreams, obsessions and quirks, including violent, strange and often disturbing distortions of faces and figures to represent what he saw as their psychological reality. So there he was in his Paris studio, making sketches but unable to come up with a satisfactory idea.

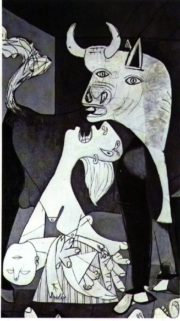

Then, on that ordinary Monday of 26 April 1937 — market day in a small, undefended rural town very far from Paris in every way — the elite Condor Legion of the German Luftwaffe suddenly and completely unexpectedly rained down wave after wave of its most powerful bombs. This massacre and destruction, widely reported in Paris and elsewhere with horrifying photographs, startled the world, including Picasso. Those scenes mustered his own personal obsessions of violence and distortion and framed them in the context of the struggle for life of a nation, so that he was able to produce in a very few weeks his powerful big painting of horror, in the starkest black, white and grays. The painting represented not just that town for which it was named (and which Picasso had never seen) but the cruelty, dismemberment and agony, the satisfaction on the unthinking face of a great bull, the despair of a mother holding her dead child, the mutilation of feet and hands, the explosion — ambiguous, either a bomb, or the sun, or a lamp — the psychological reality of a war by the immensely powerful against peaceful living, thinking, suffering humans.

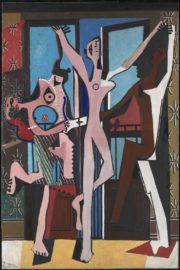

We had seen that great canvas several times, both before and after it was returned to Spain (from the Museum of Modern Art in New York) and mounted in the Reina Sofía Museum. And we had seen an earlier show in the Reina Sofía which placed around the painting many photographic and other images that may have influenced Picasso in particular details of the painting. But the show we saw today contextualized the work in another, and for me more powerful, manner. It included paintings and sculptures, gathered from many other collections, from the beginning of Picasso’s post-cubist phase, including the quite stunning, brilliantly colored “Three Dancers” of 1925, to give us an idea of the kind of imagery he had already developed and that then found its place in the stark black, white and gray “Guernica”. And then the work Picasso did later, when his own discoveries in that great work, or just the intense emotion he had felt as he produced it, continued to echo in his many paintings of women weeping, lovingly monstrous portrayals of his partner Dora Maar, and strange distorted animals.

The stunning air raid of one little town represented all the great horror of that world war and of all the destructive forces of humanity, against that other humanity which is Eros and mother-love, focusing and intensifying all his obsessions of Death and Love. Picasso’s greatest work? He didn’t think so. He preferred the “Three Dancers” (1925). But certainly one of his most intense, and the one that has had greatest effect in awakening a sense of that horror in viewers around the globe in the generations since, as the show at the Reina Sofía Museum also demonstrates in many documents and testimonies.

The Three Dancers 1925 Pablo Picasso 1881-1973 Purchased with a special Grant-in-Aid and the Florence Fox Bequest with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery and the Contemporary Art Society 1965 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T00729