Freedom Drivers, or, a Busy Day in Fulton, KY – a civil rights memoir

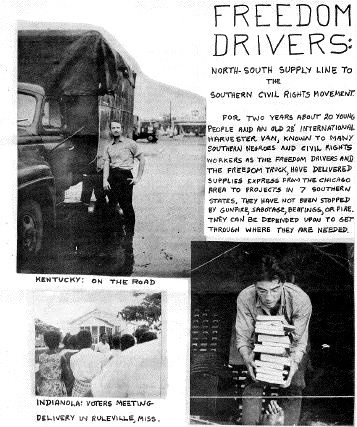

That’s me, with my foot on the running board.

I haven’t been in Fulton, Kentucky, for more than 30 years. It’s very likely a pretty nice town. Even then, in July 1966, the night of the unpleasantness, there were at least three mighty fine people living there. That’s how we managed to get out with no more physical damage than a few bumps and bruises. And of course, a ruined truck.

Back then I was living in Evanston, Illinois, where I was a graduate student in sociology at Northwestern University and, of course, one of the leaders in our new SDS chapter. Racial justice and ending the war in Indochina were our causes, so important as to make everything else — dating, drugs, studying — seem like trifling distractions. One night 24-year old Barbara Mitchell addressed our group to make an appeal for help in her project, “Freedom Drivers” — trucking goods down to SNCC offices at a camp of cotton workers (“Strike City”) on strike to demand a union. The whole scheme sounded sort of crazy — wouldn’t it have made more sense to take that energy and the money going into the truck and so forth, to send the good folks in Strike City a money order, to buy whatever they needed? But Barbara was set to go, by herself, if she had to — her husband, a professional truck driver, was working that week. Then a 16-year old high school student named Mark Kleiman (that’s he above, with the books) jumped up and volunteered. What the hell, I thought — people were getting shot down there, or run off the road and made to disappear, and here this girl and this kid were going into the deep south alone? No way! So I had to go with them.

It was a crazy scheme, and a pretty poor excuse for a truck. I took the first shift through Illinois, and as it was raining, I had to reach my arm out to push the lone windshield wiper back and forth, all night. Truck had another idiosyncracy: it had to be pushed to start. Now this wasn’t a big truck, as you can see from the photo up above (that’s me, in Fulton KY, with my foot on the running board). But it was loaded with boxes of canned good plus lots and lots of used steel filing cabinets. (Why? Somebody in SNCC had once asked for them, in the hopes of getting their office organized. We got them as surplus from Northwestern U.) So we always tried to park it on an incline.

Well, we got to Strike City without major incident. The local SNCC guys were nonplussed when they saw all the filing cabinets. “Who asked for those?” they wanted to know. But they took them. Maybe they found a use for them. Would have made pretty good barricades, I’d think. And the canned goods were welcome.

Two young fellows, not finding enough excitement in being on strike outside the A.L. Andrews plantation, asked for a lift to Chicago. Sure! Don’t remember their names, although one of them played a passive but crucial role in what happened later.

We made a brief stop in Zenobia, Mississippi. Name cracked me up — sounded like Xenophobia — but in fact it was a beautiful oasis of unphobia in those phobic times. Black and white farmers on the best of terms with one another, sitting on each others’ porches and chewing tobacco and commenting, slowly, on whatever it was they were commenting on — I could hardly make out their speech. But they fed us, and speeded us on our way, finding it completely unremarkable that we were three Northern whites and two Southern blacks passing through.

Not much happened that I remember until Fulton. I’d been doing a lot of the driving, through most of Mississippi and on, and by now I was fast asleep in the back of the truck, along with our two black hitchhikers. At least we didn’t have those damned file cabinets! I woke up when somebody started shouting at the open back of the truck, “Get out! We’ve got to push! We’ve got to get out of here, right away!” All I could tell was that we were at a gas station with an all night diner.

We jumped out, pushed, jumped back in as the truck started to move, and right away we were tearing down the highway in the black, starless night. Not even a reflection of light from our head or tail lamps. What the hell? No lights?

We hadn’t gone far when we started hearing a horrible wrenching sound, of metal against metal, then the clang of pieces of steel bouncing on concrete highway. Then the truck jerked and jolted to a halt. We jumped out, I ran around to the front, to find the engine on fire and Barbara and Mark looking at it with their mouths open.

“Get back! Get back!” I shouted. I think I tried to put out the flames with one of the old blankets we’d been sleeping on. Eventually a sheriff’s deputy came across us. He called for a tow truck, from that same gas station — Mark didn’t like that one bit, but I still didn’t know what had happened — and the tow truck left us at another gas station directly across the road, a Shell that wouldn’t open for a couple more hours. It had a picnic bench under a canopy, though, where we laid out Mark and he told us his story.

He and Barbara had left the truck at the pump and gone in for coffee. Fine. Except that, (a) Barbara had stuck onto her jacket a big “Freedom Drivers” pin and (b) one of our black passengers had decided that he wanted some coffee, too, and went in with them.

Kentucky. Hadn’t joined the Confederacy, but most of its white people hadn’t been too enthusiastic about abolition, either. And it was on the route to the deeper south. But even southern Illinois and Indiana felt like Dixie in those days.

What Mark told us: Two truck drivers had followed him into the men’s room, let him know they didn’t like white boys and especially white women sitting down with nigras, and beat him up. He wasn’t visibly bruised in his face, but he was hurting in his ribs and he was scared. Then he’d come running out of there to the truck, where Barbara and our black passenger were already waiting.

As for the truck, we found that out once the franchise owner of the gas station showed up. Jubie Henderson was maybe 23, a serious, slender fellow. We were welcome to what hospitality his gas station offered, and could stay there as long as we needed to. He gave me one of his dry shirts — for years I kept that khaki short-sleeved shirt that said “Jubie” above the pocket. It came to mean a lot to me. (In fact, I think that’s what I’m wearing in the photo up above.) And then he checked the truck.

It had been sabotaged, he said. Somebody had disconnected the oil pump, so in a very short time the engine’s own friction had torn it apart.

Later in the day the sheriff drove up to the apron of the gas station and beckoned to me for a private conference. He wanted us all out of his jurisdiction by sundown. He was not interested in our description of the two truckers, Mark’s assailants, or their rig. He just wanted us out. Which was a problem, since we had been planning to drive out in the truck.

By this time a couple of Jubie’s friends had showed up, with their squirrel rifles, out to kill time and a few small animals. Jubie, they knew, couldn’t be distracted by such pastimes, but they liked to joke with him. When they heard about the sheriff’s visit, they reinforced Jubie’s firm view that the gas station was his, and no sheriff could tell him who his guests could be or how long they could stay. One of these boys even lifted his rifle and said they would defend Jubie’s right to extend his hospitality. I tried to dissuade them — a gunfight in a gas station seemed a mite imprudent.

Finally one of these boys got hold of a car, and drove us all the way to Cairo, Illinois. It was a good piece to drive, and we were mighty grateful. Cairo was a big enough town that Mark could find a bank where his father had wired him some money, enough for all five of us — Mark, Barbara, me and the two Mississippi strikers whose names I don’t recall — to catch a bus to Chicago. Jubie took good care of that truck, installed another engine once Barbara was able to raise enough money to buy one, and the Freedom Drivers kept on trucking. But I didn’t. There was a war to stop, and I could do that just as well in Chicago.

(First posted in 1996)