In the Low Countries, 3: Art in context

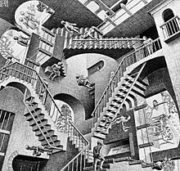

One of the benefits of our journey was seeing famous and familiar art works in contexts that made them new and required a fresh interpretation. Seeing reproductions in books and the Internet or, if we’re lucky, the originals in a museum can be no more than a start to understanding it. Being there, in the Netherlands and Belgium, feeling and smelling the salt air, the light, sensing the geography, moving through the urban and rural spaces where the art was produced, added layers of complexity, provoking new questions and complicating whatever simplified interpretation we may have entertained about an image as familiar as Vermeer’s The Girl with the Pearl Earring or Escher’s Relativity (image above).

In the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague, we could view works of old masters including Rubens, Rembrandt and their colleagues, which helped place them in their artistic context — that is, the subjects and the techniques shared by artists of their time. We also saw there, in its artistic context with other works, the original of Vermeer’s The Girl with the Pearl Earring. Getting to Delft (a short train ride from The Hague) put us in the physical, geographic context. The oude kerk and the nieuwe kerk and a walk along the kanaal that gives the city its name (delft comes from delven, “to excavate”, like our English word “delve”) seemed to bring to life the world of Vermeer and his colleagues — despite all the more recent tourist paraphernalia. (For more on Delft and how it got that way, check out my review of Tracy Chevalier’s novel, Girl with a Pearl Earring.)

Also in The Hague, and jumping several centuries forward, from the 17th to the 20th, Maurits Cornelis Escher’s many prints, drawings, paintings, sculptures and photographs from different periods, along with photos and texts on his life, in Escher in het Paleis in The Hague, showed us that he was more than a clever illusionist. The exhibition, which entirely fills the former winter palace of the Netherlands’ Queen Mother Emma (1858-1934), stresses Escher’s fascination with mathematics and his devotion to an imagined purity and his delight in staring into abysses, natural or man-made, until dizzy enough to see relationships inverted. But I have a hunch that part of what drove him was his need to escape mentally as well as physically from the political irrationality and then the chaos and destruction in the world around him, in Italy, Belgium and finally the Netherlands during the war. That global chaos was also part of the context.

For a very different art movement in the 20th century, for the hundredth anniversary of the first issue of De Stijl (“The Style”), the revue that gave its name to the movement, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam has gathered and mounted many of the lesser-known works, putting the artists in their social and political, as well as artistic, contexts. (Until August 6, 2017). The best-known among them was Pieter Cornelis Mondriaan, or “Piet Mondrian” as he simplified his name in the U.S. He was already 45 and established as a figurative painter when in 1917 he and Theo van Doesburg launched their magazine De Stijl as a manifesto for extremely austere abstraction, attracting many younger artists looking to break radically with art traditions of the old Europe before the World War. The show highlights the conflicts within the group and among their several concentric or overlapping contexts. At the core, for Mondriaan and the purists, was the artistic context, the dialogue with and rupture from other familiar styles of art. And within this core group, individual ambitions, rivalries and degrees of market success stirred the usual tensions. All those tensions were exacerbated by the larger context, the psychological shocks of the Great Depression with its the breadlines, marches of the unemployed and the battles in the streets, leading to the Second World War and its disastrous consequences for the Netherlands and much else.

The show in the Stedelijk illustrates these tensions by devoting much of its space to De Stijl’s great “defector”, Chris Beekman (1887-1964). Beekman started out as another pure and austere abstractionist in Mondriaan’s line, but as the times got harder in the city around him, he couldn’t reconcile his anarchist convictions with De Stijl abstraction, thus going from this, in 1920:

Beekman, Compositie, 1920

Chris Beekman, Forbidden demonstration,1934

to this, in 1934:

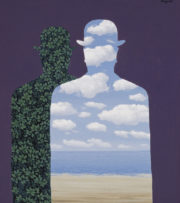

Finally, a word about another 20th century artist from these Lowlands, René Magritte. Or no, not a word, just an image, as he would prefer:

La belle société, 1962

To learn more, check out these websites:

Mauritshuis

Escher in het Paleis

M.C. Escher official website

Stedelijk Museum

Chris Beekman

René Magritte Museum

Bandes dessinées