The sociological imagination — in fiction

I was startled recently by the recommendation that authors “brand” ourselves to sell our work, which I first saw in a symposium in the Spring/Summer 2015 issue of the Authors Guild Bulletin. It has also become commonplace in blogs I found quickly by a Google search (author + brand).

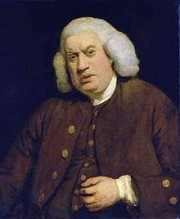

It sounds crass, as though we were producing merchandise, to be packaged and presented for optimal marketing. Because as writers have known since long before Doctor Samuel Johnson (who famously “wrote for money”), a special and recognizable voice, style and themes are not merely devices to catch the attention of editors, publishers and readers. Rather they are the essence of a writer’s identity.

But this discussion of “brand” has led me to ask myself, What is distinctive about my writing? And I think that, more than anything else, it’s my sociological imagination. That is, I am working in an unrecognized genre, “sociological fiction”. It’s not that I am alone, or that this genre is unpopulated — Don DeLillo works here, and Mario Vargas Llosa, and many others — but that you probably won’t find a shelf with that label in your bookstore or such a category in Amazon.

I know that my “voice” — the word choice and phrasing, which set a tone — is recognizable, but it’s not calculated; it’s simply the way I think and talk, without a lot of reflection or hesitation. (Which is the way it should be — when you start calculating how sarcastic you want to be, for example, or how polite, or how formal, all liveliness leaks out of your prose.) But it’s not “voice” that I think sets me apart.

Then there’s “style” — by which I mean the ways I tend to frame an essay or a story. This is more deliberate, something I have worked to develop. It would be tedious to describe, and unnecessary — all you need to do is read a couple of my stories or essays to see how I try to organize and pace images and ideas, to make each support the others and reach a satisfying conclusion. A lot of writers try to do the same thing.

And finally, my “themes”, what I write about. This, I think, is what is most distinctive about my work. Since I’m no longer on a payroll producing articles on demand for a newsletter or magazine, my themes are entirely my choice. And these are almost always, or maybe always, sociological. It’s not just that I’m interested in social relations — every fiction writer has to be — but that for me, how the system works and, particularly, what it would feel like to be living that situation, are the main thing.

Thus, I think of my novel A Gift for the Sultan, about the interactions of Ottoman Turks and the Greek-speaking, Christian Orthodox rulers of Constantinople in 1402, not as historical but as sociological fiction. It is historical, of course, in the sense that the events took place a long time ago, but I’m not just trying to give colorful detail about what happened (we know that already, or could easily find out). Rather, I’m seeking to understand the complex commercial, political, social and even amatory relations when two radically different cultures share a territory and must seek to understand, or sometimes try to annihilate, one another. So, yes, the novel is about Constantinople in 1402, but it is also about Sarajevo in the 1990s, or Zimbabwe in the 1970s or Mexicans and Yankees in the American Southwest in the 1800’s, or Israelis and Palestinians today, and maybe can even hint at some things we need to know about sectarian and political conflict in Syria and Iraq.

My current novel, The Bookbinder, is about the Paris Commune of March to May 1871, but it also is more sociological than historical. It is a case study of a very condensed (just two months), very large scale (in a city of nearly 2 million people, then one of the most important cities in the world) revolutionary event. It is thus a way of examining revolutionary aspirations, coalitions and frustrations that are relevant not only to the history our world has lived, but the history we are making now.